Shag carpeting. Eight-track tapes. Missing an important phone call because you weren’t home to hear the phone ring.

There are few anachronisms from the 1970s that most Americans from that era will not miss. It was a time of long gas station lines, itchy polyester double-knit suits and TV options limited to three networks that signed off each night with a warbled recording of the Star-Spangled Banner.

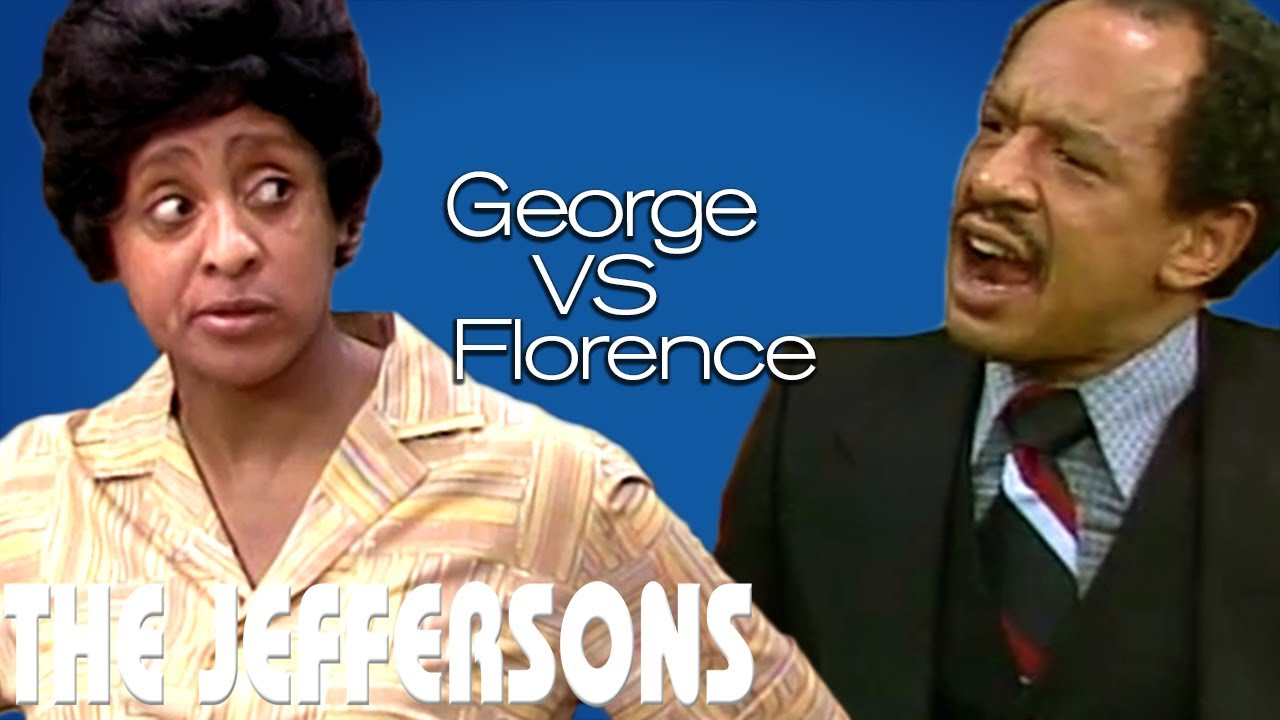

But as a Black child of the 1970s who grew up on shows such as “The Jeffersons,” I miss one storytelling element from that era that seems to be missing from contemporary Black TV series: hope. Not a naïve hope, but a muscular type of hope that maintained that though racism was persistent, America would eventually transcend its racial divisions.

Watching clips from popular 1970s shows like “Room 222” and “The White Shadow” is like stepping into an alternative universe. White and non-White characters tackled racial issues with a boldness and nuance that wouldn’t be allowed today. They strived together to create integrated neighborhoods and schools. They thought people could change, and so could America.

“There was this moment of hope in America where we actually believed that we could confront and deal with centuries-long problems of race, gender and class,” says Rodney Coates, a sociologist, poet and professor of critical race and ethnic studies at Miami University in Ohio.

“They weren’t stuck in fatalism,” Coates says of ’70s shows that addressed race or featured mostly Black casts. “They weren’t stuck in the notion of it’s always been this way, and we can’t change it.”

I bring up Black TV shows from the 1970s because I’ve been told my nostalgia is misplaced. In recent years, many cultural critics have claimed we are in a new “golden age of Black television.” They say there’s been a renaissance in Black TV, driven by a new wave of Black creators who are finding fresh ways to explore the Black experience.

Yet to me and some scholars, critics and TV producers, something is missing. Some recent shows confuse hopelessness with being authentically Black. Others display what one scholar calls an “apolitical multiculturalism”— they feature Black and brown actors but rarely explore their characters’ race or ethnicity.

And few share the tone of their 1970s predecessors — there’s little of the “enduring optimism” reflected in “Movin’ On Up,” the “Jeffersons’” theme song, which became an aspirational anthem for Black America.

Some say TV is ‘Blacker and bolder’ than ever

At first glance, it’s hard to argue against this being a new golden era for Black television. I’ve praised this era myself. I once insisted that the “the most eye-popping elements in a recent wave of sci-fi and horror TV shows featuring Black actors are not the special effects and supernatural creatures, but the multiracial casts and casual acceptance of racial differences.”

There also are more Black creators in television today, including producer Shonda Rhimes (“Bridgerton,” “How to Get Away with Murder”) Donald Glover (“Atlanta”) and Quinta Brunson (“Abbott Elementary”).

Back in the 1970s, virtually all of the Black-themed shows were created or co-created by White men like Norman Lear, the legendary television producer and screenwriter behind such shows as “Good Times,” “The Jeffersons” and “Sanford and Son.”

Good Times, a CBS television situation comedy. Premiere episde, February 8, 1974. Pictured from left is Ralph Carter (as Michael Evans), Esther Rolle (as Florida Evans), John Amos (as James Evans, Sr.), Jimmie Walker (as James ‘J.J.’ Evans, Jr.), BernNadette Stanis (as Thelma Evans).

“Good Times,” another CBS comedy, premiered in 1974. Its cast included, from left, Ralph Carter (as Michael Evans), Esther Rolle (as Florida Evans), John Amos (as James Evans, Sr.), Jimmie Walker (as James ‘J.J.’ Evans, Jr.), BernNadette Stanis (as Thelma Evans). CBS/Getty Images

And truth be told, some of those old shows relied on racial stereotypes. Actor Jimmie Walker’s J.J. character in “Good Times” strayed into the buffoonery zone with his incessant catchphrase, “Dyn-o-mite!”

Eric Deggans, a TV critic, said last year that some of the Black sitcoms from that era unintentionally made living in impoverished areas “look livable and even fun, as opposed to the issues that they (Black people) really faced.”

Contemporary Black TV shows rarely make those mistakes, some TV critics say.

“Today, Black shows are more authentically Black and bolder,” says Jeffrey Wray, a director, producer and actor. Wray says an all-White writing room telling stories about Black people is now looked on with suspicion. He points to the success of success of HBO’s “Insecure,” a critically acclaimed drama starting Issa Rae about the friendship between two contemporary Black women.

“Insecure’ was clearly Black and female in spirit, tone, story and execution, and the writers, producers and behind-the-scenes team was made up almost exclusively of Black and Brown creatives,” says Wray, who is also a film studies professor at Michigan State University.

Why being hopeless is not the same as being Black

And yet there is a part of me that now wonders if the contemporary Black shows are as Black and bold as they claim to be, and if some are being too casual about the acceptance of racial differences.

Consider the frequently misunderstood word: hope. I, along with some other TV critics and writers, don’t see a lot of it in contemporary Black shows. “Abbott Elementary,” which follows a dedicated group of teachers valiantly trying to reach students at an underfunded public school, expresses some of that hope.

But “Abbott’s” optimistic tone is an exception and not the norm for popular, Black-themed TV shows in recent years, several TV critics and scholars I talked to say. Hope has become just another four-letter word for a lot of contemporary shows that deal with race.

One critic cited a Black-themed show that set the tone for contemporary TV series that address race: “The Wire.”

The creators of the acclaimed HBO series, about the interplay between a colorful group of criminals, police officers and politicians in an inner-city neighborhood in West Baltimore, is widely considered one of the most realistic portrayals of Black life ever put on TV. Still, few if any of the Black characters in “The Wire” ever really escape the city’s cycle of crime, violence and corruption.

If “The Sopranos” got people talking about <a href=”http://www.cnn.com/2013/05/06/showbiz/golden-age-of-tv/”>a new “TV golden age,”</a> then “The Wire” was held up as proof that <a href=”http://www.newsweek.com/why-tv-better-movies-105071″ target=”_blank” target=”_blank”>TV had gotten better than movies</a>. Hailed as novelistic and DIckensian, the show focused on the social and cultural forces that collide in a big city — Baltimore, in “The Wire’s” case — and what makes progress so difficult.

“The Wire,” which aired from 2002 to 2008, was held up as proof that TV had gotten better than movies. The show focused on the social and cultural forces that collide in a big city — Baltimore — and what makes progress so difficult. Action Press/TASCHEN

This pessimism was baked into the show from the very beginning. David Simon, the show’s creator, once described the series’ storytelling philosophy: “This is going to be a cruel world and nothing is going to get fixed that matters systematically.”

As someone who grew up in the neighborhood where “The Wire” was set, I’ve frequently written about how the show unintentionally sent this message: The only authentic Black story about race is a hopeless one.

Coates, the critical race studies professor, says “The Wire” set the tone for contemporary shows that address race or feature Black casts.

“Part of the problem is that there is way too much time spent ‘rediscovering’ the problems — police brutality, addiction, abuse — and too little time experiencing the solutions, the victories, the success stories,” Coates says.

Such TV series ignore the rich tradition in the Black community of embracing a certain type of hope. Not the Hallmark-card kind of naïve hope, but something sturdier.

It’s the hope that enabled enslaved Africans to survive the Middle Passage and the barbarity of slavery; the hope reflected in the negro spirituals that still move people around the globe; the hope that columnist E.J. Dionne Jr. — paraphrasing former President Barack Obama — described in a recent column as a “demanding virtue, not a sunny disposition.”

“It accepts reality, acknowledges obstacles and insists,” Dionne wrote, “as the bard of hope Barack Obama put it, ‘that something better awaits us if we have the courage to reach for it and to work for it and to fight for it.’ ”

TV in the 1970s showed glimpses of a more promising tomorrow

This is the hope I saw in Black-themed shows of the 1970s, as well as another popular show whose creators demanded that its cast and neighborhood setting be racially integrated: “Sesame Street.” Others saw this hope reflected in ‘90s Black sitcoms like “Martin” and “The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air.”

One of my favorite shows from the 1970s was “Room 222.” The series followed Pete Dixon, an idealistic and impossibly suave Black history teacher played by Lloyd Haynes. Dixon taught lessons in tolerance at an integrated public high school in Los Angeles, where he and other educators often debated issues like racism, sexism and homophobia.

Lloyd Haynes as Pete Dixon in “Room 222”.

Lloyd Haynes as teacher Pete Dixon in “Room 222.” ABC Photo Archives/Disney General Entertainment Content/Getty Images

I still occasionally watch the opening credits montage of “Room 222” for an injection of hope. It depicts smiling Black, White, and Asian students strolling happily through a sun-dappled campus on their way to morning class. As a kid who grew up in racially segregated public schools (there was only one White student in my Baltimore high school), I was fascinated watching this preview of what this country could be.

So was Billy Ingram, an author and creator of the entertainment website TVparty!. He wrote a 2013 essay in which he said “Room 222” may be even more enjoyable to watch today.

“The [“Room 222”] storylines provided a fascinating glimpse at a moment in history where society was rapidly evolving toward a promising tomorrow—that’s what we thought anyway,” he wrote.

When “Room 222” aired, from 1969 to 1974, Ingram was growing up in a racially segregated Greensboro, North Carolina, living with parents who opposed integration. Public schools were just starting to desegregate, and tensions were running high. For him, seeing White and non-White actors on “Room 222” work out racial issues and earnestly strive to live together was a revelation.

“It introduced me to ideas and thoughts that had not occurred to me,” Ingram says. “The country as a whole was making tremendous progress. It felt like we were coming together.”

Ingram’s nostalgia for the early ‘70s may seem odd to those who remember that era. The 1973 oil embargo sent shockwaves through the US economy. The US military was humbled by losing the Vietnam War. And that idyllic “Room 222” opening? White parents in cities like Boston were watching another channel. They staged angry protests against desegregating schools.