His struggles to maintain his identity while making it in Hollywood and the joys of Victor Newman

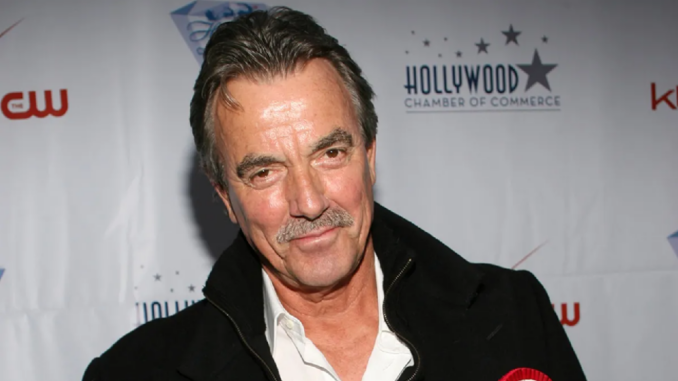

For actor Eric Braeden, best known as Victor Newman on the television soap opera The Young and the Restless, his past literally caught up with him during the making of 1997’s Titanic, in which he portrayed John Jacob Astor IV. There he was, participating in the sequences involving the sinking of that vessel, when he heard a single word from James Cameron: “Never.” Turning around to see the speaker, he realized it was the film’s director, who followed up with an explanation: “The last line in Colossus.”

Released in 1970, Colossus: The Forbin Project, and its tale of a computer gaining sentience and essentially taking over the world, saw Braeden portraying its creator—and inadvertent architect of humanity’s downfall—Dr. Charles Forbin. While not a box office success, it nonetheless gained a huge cult following over the decades, and Cameron revealed himself to be a part of that cult.

It also seemed like the perfect place to start a conversation with Braeden, who was born Hans-Jorg Gudegast on April 3, 1941, in Bredenbek, Free State of Prussia, Germany (now Schieswig-Holstein, Germany.

WOMAN’S WORLD (WW): There’s a story to you being cast in Colossus, isn’t there?

ERIC BRAEDEN: I was in Spain at the time with my wife, and we were with Esther Williams and Fernando Lamas while we were doing A Hundred Rifles. I flew from Spain back to LA to do the screen test for Colossus. Two or three days later, the agent called and said, “They loved it. Lew Wasserman [then head of Universal Pictures] loved it.” Of course I was ecstatic — that’s about as happy as you can get in this business, to star in a picture. For me to star in an American picture was an absolutely extraordinary feeling. In the next breath, though, they said, “But they want you to change your name.” I tell you, I’ve never experienced such an emotional swing as in that 10 seconds, from complete elation to total dejection.

I was so emotionally distraught by everything that happened prior to actually doing the picture, and there were a number of issues involved which pissed me off. Most of all, getting rid of a name is like getting rid of one’s identity. Number two, of course, was an enormous amount of prejudice toward Germans that is typical of an Anglophile country. At the same time, I also knew the reality and conceded to Universal’s wishes. I chose Eric from a family name and Braeden from the German village I’m from.

WW: Before acting, soccer was actually an important part of your life.

EB: Yes, it was. I was a part of my high school team when we won the National German Youth Championship. After I graduated [in 1959], I decided to go to America. I saw the United States as a land of opportunity, but also as the land of adventure, the land of cowboys and Indians.

I arrived in New York by boat and spent a few days there before going to Galveston, Texas, where I worked as a translator. A few months later, I went to Montana where I was hired as a cowboy and worked on a ranch, though I must admit that that lifestyle began to lose its appeal. So I attended Montana State University, worked at a lumber mill and participated in ROTC practice.

WW: At which point you and another student documented a boat trip up the Salmon River in Idaho, which became a film documentary.

EB: Riverbusters. I went to LA to find a distributor, but decided to stay there given that I had learned German actors were in demand for TV and films. So I got an agent and began to act. My first film was Operation Eichmann. Then I did television, starting with Kraft Suspense Theatre, and from there I played the Prince of Wales in Sartre’s Kean. I also performed on Broadway in The Great Indoors with Curt Jurgens and Geraldine Page. And it was Curt Jergens who gave me this advice: “Listen, you will play nothing but Nazis in Hollywood. That is the fate of all German actors.” I told him, “Well, I’ll be the first to do something different.”

WW: The irony, of course, is that you ended up playing Captain Dietrich in the television series The Rat Patrol. What was that experience like?

EB: The making of Rat Patrol was largely fun, although it was a cartoon, of course. I knew that from the beginning. The material was a joke. The very opposite of what they showed was true. Rommel had a small army in North Africa and beat the British Army for a long time, but on the show, they reversed it completely. Still, I tried to humanize the character as much as I could.

WW: Let’s return to Colossus. Your co-star, Susan Clark, admitted that she was frightened by the project because she felt the “computer stuff” would mean something someday. Did you agree?

Eric Braeden: I did. The aspect of the film that struck a chord with me was the specter of a third World War. I say that because I remember the bombs of the Second World War; I grew up with them. Colossus captured the fear of a very possible mistake in the computerized arsenal that both sides had and have. That frightened me, because in reality it could happen at any time. Things have changed, of course. Then it was nuclear arms, now it’s not. Now it’s about using technology to obviously destroy as much as they can in Western democracy, and they are succeeding brilliantly so far. I don’t think they will win in the end; I think America is strong enough and tied strongly enough to its constitution for that to never happen. Good and freedom and democracy are things that cannot be put asunder — not for long — although people try.

WW: Was the making of the film itself enjoyable?

EB: It was an unmitigated joy, thanks to director Joseph Sargent, producer Stanley Chase, James Bridges’ screenplay and the efforts of cast and crew. All of this despite the fact I am not a fan of science fiction. I remember at the time it was the height of the Bergman and Fellini films and those were the kind of things one wanted to do. However, I always was intellectually enormously interested in this subject matter. Not emotionally, because it’s hard to grasp, obviously, because of the “unlikelihood” at the time that two machines would talk to each other. That was very hard to grasp. That piece of unreality was difficult to handle. However, I have enormous respect for the people who worked on it. Not a single bad memory.

WW: The film was not a box office success, yet you felt that its lack of box office taught you some life lessons.

EB: I had an eerie feeling when I did Colossus. Here I was starring in a Universal picture. I don’t know if you know what that means, but suddenly you’re picked up by a limo. You must juxtapose that with the struggling existence that most actors go through, doing menial jobs and constantly being turned down for work.

Suddenly you’re starring in a film and the transformation is so extraordinary, you haven’t a clue what’s going on. It manifests itself in so many small ways. First of all, it’s in Variety and The Hollywood Reporter, so everyone in the loop knows about it. They look at you differently, they approach you differently, because this means potential power. If that film makes it, you have power. What does that mean? I’d better kiss his a– now. People who didn’t even know you existed before are blowing smoke up your a–. In restaurants you get tables suddenly — I mean suddenly. You sit in the commissary in one of the big studios and people who never even acknowledged your existence are saying, “Hi, Eric, how are you? How’s everything going?” It’s just amazing.

At the same time, it fills you with insecurity, because you’re not prepared for it. And the most painful part was watching your friends start changing toward you. People that you felt comfortable with, that you felt secure with, that are a secure anchor, all of a sudden change toward you, because you’re a “star” now. It is such an interesting and strange psychological interchange that happens between those who knew you before and they all say, “I knew him when.” You want to say, “Don’t say that s—, we’re friends. Why are you saying that?” It gives you an eerie feeling. I remember vividly while I was doing Colossus having that happen and almost feeling depressed about it. You feel the ground underneath you start giving away. You have all of a sudden been catapulted into the stratosphere. I have always said that the Screen Actor’s Guild or the studios should take all actors who are beginning to star in films and give them the number of a good therapist. I never went to one, but I wish I had then, to be quite frank with you. It is a truly frightening experience and if you’re insecure and don’t know what to do with it, you can become a monster.

WW: This was all before the release of Colossus. What changed afterwards?

EB: In a short period of time, it goes from, “Eric, my God, how are you?” to “Oh, yeah, how you doing?” You have no idea how blatant some people are. It’s stunning. Remember, that aspect in the life of someone who becomes a star in any field is one that is so unexamined, yet explains so many things when you try to wonder why an actor or someone in the limelight suddenly behaves in a bizarre manner. They will never, ever talk about it, and it pisses me off. Either the star isn’t honest about it, they don’t talk about it, or people don’t ask about it, because it’s too personal.

One positive that came from being cast was the offer of two additional starring roles at the time. But then the recession took its toll on everyone, including Hollywood, and the number of productions had been whittled down to practically nothing. As a result, my projects came to a halt, and that taught me something else. I was with a top agency in town, they approached me after Colossus and they were the Rolls Royce of the agency business. They handled all the big stars and they said to me, “You’re going to be a big star one day, but you’ve got to be patient because they won’t be making films for a while.” Well, I had a child by that time and needed to make money.

The progression for an actor was originally to guest star in TV, to perhaps star in a television series and then go on to film. But once you star in a film, you do not go back to television. So my hands were tied. All of a sudden, the money runs out, I’m sitting there with a child. So what do you do? You start guest starring again, but that was a no-no in the business.

WW: You did do a number of guest spots on series like The Mary Tyler Moore Show and Kolchak: The Night Stalker, and appeared in the film Escape from the Planet of the Apes, but then you moved into professional soccer as part of the Maccabees.

EB: By that time I was so tired of playing bad guys. They’re just so one-dimensional. But I enjoyed working on the Apes film. Producer Arthur Jacobs was a gentleman and so was director Don Taylor. The cast was wonderful, so in that sense it was wonderful. Plus, I didn’t have to put on one of those damn masks. The problem is that those three years after Colossus were rather bitterly disappointing. I saved myself by playing sports. We won the 1972 to 1973 National Soccer Championship. I was actually playing competitive soccer during all that time secretly. So I quickly forgot about all this Hollywood crap, because I was so involved in soccer.

WW: You obviously appeared in numerous shows and had small roles in movies, but would you say Titanic was more prestigious?

EB: It’s a small part, but I had a feeling that this was a historic film. I thought this is one of those films where it doesn’t make a difference what you play. It’s one of the most impressive things I’ve ever experienced in this business. No, the most impressive time I’ve ever spent. James Cameron is a genius. That word is bandied about loosely in Hollywood, but I think it applies to him. I have never in my career been in the presence of someone so extraordinarily bright, with an energy that is boundless.

WW: Of course, in 1980 Victor Newman and The Young and the Restless entered your life and has been a part of it ever since, which is pretty incredible.

EB: I remember the first time I told people I was doing a soap and they reacted as though I’d contracted a disease. In other words, when you run into actors that you’ve seen for many years, you sort of hug each other and there’s a certain kind of unspoken warm recognition of the fact that you both have survived. Meaning it has been tough at times. I’m not talking about megastars. They’re a different story. They’ve made so much money very often that who gives a f— if they ever work again? Those of us who weren’t megastars, and aren’t megastars, who are working actors, we know how tough it is to survive in this business.

WW: How did you get involved with the show?

EB: Dabney Coleman, a friend, spent some time on soap operas and he pushed me toward it. But I have to say that I despised the first year because the working parameters were so limited. But then, my wife got me to start looking at turning all of that into a positive experience. The negatives were a high of 62 pages of dialogue a day and no time to rehearse, but I started to look at them as obstacles to be overcome. From that moment on, I haven’t looked back. And I still get turned on by trying to make something real.

You stare so much dialogue in the face sometimes that you need to make it your own. I have never tired of that. It is something that has basically enthused me almost all of my acting life, so it makes almost no difference what vehicle it is. And I earn very good money, let’s not ignore that. If I made what I’m making here doing Shakespeare, I’d be doing Shakespeare, but it ain’t the case.

WW: Helping you change your view was also the personal appearances you made, right? Some of them had more than 15,000 people show up.

EB: To be honest with you, all of that recharged my batteries, because I realized that I did make a difference. A lot of people in Hollywood don’t realize that what they do does make a difference in people’s lives. They’re entertained by it, and I cannot begin to tell you the testimonials after all these years. People call you from hospitals; people are dying and the last thing they want is a word from you. As a result, you are reminded of the basic religious ethics you grew up with. I was never serious about it, but one thing that did appeal to me about the whole Christian mythology was the idea of giving of yourself; of loving, if you want, a fellow human being and, primarily, someone who is in need. If you can overcome the cynicism, if you’re intelligent and really think about this profession, you realize you’re a part of something extremely important.

For a long time, the only films that interested me were the ones that had a social and political reality to it as a base. But you have to get over that. You reach a point where you say, “We are here to entertain and there is a value to just entertaining people.” An enormous value. Once I reconciled to that, and once I realized that I could make people cry and laugh and be upset and happy, it was a great feeling. One should be humbled by it. Most actors, like any artists, are basically insecure because you’re dealing with something very fluid. We’re constantly grasping to mold it into something, so there’s a certain insecurity and questioning in most of us. A lot of us are angry about certain circumstances we grew up in, which is why we became artists in the first place. So there’s a tendency to then become cynical, but you’ve got to realize that you are almost a vehicle in a sense. You’re a conduit and that’s a good image to have, because you don’t take yourself so damn seriously.