From Broadway to Mayberry, the friends shared a bond—Knotts’ brother-in-law shares the inside scoop!

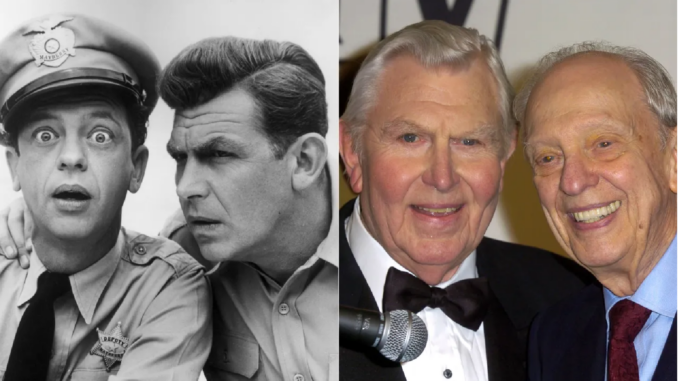

Certain pairings on television shows are just magic—when the chemistry between a pair of performers surpass anything the writers could have imagined and bring a whole new element to a series. We’ve seen it with Lucille Ball and Vivian Vance on I Love Lucy, William Shatner and Leonard Nimoy on Star Trek, Ron Howard and Henry Winkler on Happy Days and, of course, Andy Griffith and Don Knotts on The Andy Griffith Show. In all of these instances, the friendship established between the performers transcended the time of their shows and lasted the rest of their lives. In the case of the latter, several years ago journalist and author Daniel de Vise brought to the world his book, Andy & Don: The Making of a Friendship and a Classic TV Show.

No doubt serving as an entry point to that book for de Vise is the fact that he was the late Knotts’ brother-in-law and got to know him better than a lot of other biographers have been able to. In the following exclusive interview, we look at the decades-spanning friendship between Andy Griffith and Don Knotts through the reflections of the author himself.

WOMAN’S WORLD (WW): It’s amazing how well the gentle comedy of The Andy Griffith Show still works all these years later.

DANIEL DE VISE: As a viewer, I can’t think of another black and white show from that era other than Dick Van Dyke, The Twilight Zone and I Love Lucy that holds up artistically to the point where you’d still want to watch them. And as far as a fandom is concerned, it’s unparalleled. I don’t think another show from the black and white era has annual conventions with 30,000 people flocking into a town every September. Nothing like that.

WW: In writing the book, were there any revelations for you about its continuing appeal?

DDV: If you go back a hundred years, our ancestors were living in small-town Americana if not on a farm, so if you had kin in the United States in the 30s, 20s or teens, more likely than not they were on a farm or in a little town. So the connection is that these two guys — Andy Griffith and Don Knotts — really built that show around their shared memories of small-town Americana, Andy with North Carolina and Don with West Virginia.

There is an almost literal one-to-one correspondence between Mayberry and Mount Airy, North Carolina, where Andy was born. But the show is also informed heavily by Don’s hilarious stories he would tell of his own childhood in Morgantown, and maybe even more so, these Knott’s family farms that were across the border in rural Pennsylvania. All that’s in that show and that’s the connection. That’s why I think almost anybody in this country who has any of that in their background can connect with that, not to mention all the people who still live in places like that in the United States to this day.

WW: Is it a reach that, given the challenging times we’re in, it somehow makes the show even more embraceable?

DDV: A guy who’s writing a doctorate interviewed me a few months ago and wanted to know how I thought they would’ve dealt with the COVID pandemic in Mayberry. What occurred to me is that they didn’t handle heavy dystopian Battlestar Galactica-style themes in Mayberry and we know for a fact that The Andy Griffith Show did not get into civil rights, which was a huge issue in the 1960s when the show was actually filmed. They didn’t get into any of the heavy societal issues that were going on at that time. Instead, they reached into the past, back into the 30s and, again, small-town Americana. But that’s not really answering your question.

To answer it more directly, when COVID broke out, my wife and I found great solace in watching episodes of The Andy Griffith Show. It just seemed natural that watching a little Mayberry would calm us down. At one point we were switching between that and the original Bob Newhart Show, which is a very calm, placid comedy from the ‘70s. A pandemic is not the time to be watching Battlestar Galactica or The Dogs of War. The Andy Griffith Show is a balm. I’m sure Hollywood in the ‘60s was a very busy, fretful place, so it’s kind of amazing that they were able to project such calm on that program.

WW: Despite the fact that you’re Don Knotts’ brother-in-law, did you go into this book with one idea of who Andy and Don were and come out of it with another?

DDV: Obviously I knew more than the average fan going in, because I knew Don and his wife was my sister-in-law and he was my brother-in-law. And I knew more about Andy because of that connection. So I knew what to expect when I sketched out their stories, but there was plenty in the way of revelations.

They had three marriages each and both of them struggled with fidelity at times. Andy had a temper, which I think manifested more behind the scenes, not necessarily on the set. In Don’s case, he struggled some with addiction in his lifetime. Both had a weakness for dating co-stars and that kind of thing. Andy had this long-term extramarital relationship with Aneta Corsaut [Helen Crump on The Andy Griffith Show], which I guess I revealed in the book. I didn’t include it just for salacious reasons, but rather because I saw it as a major love relationship in his life, just like his love relationship with Barbara Bray Edwards, his first wife.

WW: It’s an interesting line to walk in that you’re trying to dig deeper, but at the same time fans probably don’t want to know all the dirt about Andy and Don.

DDV: In Facebook groups, every so often somebody will tag my name and I’ll see that somebody’s new to the group and asking, “What have you heard about this Andy and Don? Is it good? Is it tabloid? Is it bad? What does it say about these men? Is it going to burst my bubble?” Invariably, somebody rises to my defense and says, “Well, you won’t look at the two men exactly the same after you read it, but when I read it, I walked away with all the more admiration for their accomplishments as actors, as comedians, and even more impressed with the show. But if you read Andy and Don, and if you’ve never read one of these literary biographies that’s really warts and all, you might be a little surprised. Maybe you’d best leave that lie and just think of Andy and Barney and those characters and let that be all about the guys.”

WW: Would best friends be an appropriate term for the two of them?

DDV: That’s a really good question. I think that by the end of their lives they mutually regarded each other as best friends. At earlier times as they drifted in and out of association with each other, the closeness of their relationship might’ve ebbed and flowed a little bit. I want to say that the years they were together in Hollywood working on the show, they were intensely close all the time. That’s what I call a Hollywood friendship, probably like Shatner and Nimoy being together on the Star Trek set hour after hour after hour after hour. And just like anybody who’s ever gone to college or gone to war with somebody, that really bonds you. But as they drifted into separate projects in the ’70s and ’80s, who knows what Don would have said if I grabbed him on the set of Three’ Company and said, “How close are you to Andy, really?”

But later, especially when Matlock happened and as The Andy Griffith Show gained this status of an iconic piece of American popular culture, in a way it was their destiny to be best friends. By their autumn years, each had this enormous respect for their friendship and for what they’d meant to each other and what their friendship had meant to that show. I can tell you that every moment when I was writing that book, I kept that friendship front and center and how deep it really was. Older guys barely have any friends, but these two definitely had a powerful friendship. It was certainly enough to fill the book.

WW: They’d worked together prior to the show. When would you say that there was the realization of a real connection or between them?

DDV: Each one of them had kind of grown up in the South and made a pilgrimage to New York. By the time they met, they were both Southern guys in New York and there weren’t a lot of Southern guys in New York, at least not in the theater and television and radio scene. So that right there set them apart, and I believe they both tried out for this play, No Time for Sergeants. And Andy, through his own machinations and great ambition landed the main role and that was a huge name project. it was sort of like a Hamilton-level production of the 1950s. It was a bestselling book that became a Broadway play and a movie. So Don landed a much smaller role in it, and they met, I guess in the rehearsals, and hit it off immediately. I see them as being pretty close all through that era when they were trying to make it in New York.

And then when Andy reaches a point where he’s kind of used up his capital as a theatrical actor and as a leading man in cinema, he retreats into television. He’s in the midst of putting The Andy Griffith Show together and Don telephones him and pitches, “I think you need a deputy.” Andy thought that was a great idea and they wind up together and that connection is made.

WW: What’s amazing is the instant chemistry you sense between these guys when they come together on screen.

DDV: In the play No Time for Sergeants, they only had one or two scenes together, but they had an immediate comic duo sort of chemistry even then. That’s why Don gets hired for the film as well, because this chemistry revealed itself in the Broadway play. And by the time they got together for the Griffith show, surely Don understood, and I’m sure Andy did as well, that they had the makings of a brilliant comedy team like a Martin and Lewis.

WW: But that team in essence broke up when Don left after five seasons. What impact do you feel Don’s departure had on the show?

DDV: The Griffith show becomes sort of a shell of itself. Andy looks sort of bereft. He looks bored, he looks cranky, he looks unfulfilled, both in terms of the dwindling artistry of the show, in terms of his best buddy not being there anymore, and the comedic team being broken up. It’s like Lewis without Martin or Bing Crosby without Bob Hoped. And when I was writing this book, I was afraid to say anything real critical about the show, although I do say that I don’t think the color episodes are all that good. There’s some good ones, but the thrill is gone, to paraphrase B.B. King. In terms of ratings, the show did just as well. Even better at some moments in those last three years, so people kept watching it. Out of habit more than anything else.

WW: Do you think Andy and Don regretted their decisions to leave?

DDV: I look at this glass as being half-full, because Andy has this brilliant comeback — takes him a long time, but he finally has a brilliant comeback with Matlock. And Don had a very respectable run of five-year increments. He did five years on the Griffith show, roughly five years of very successful low-budget Universal films, then about a five-year run of Disney films and then he has a five-year run on Three’s Company. So, if you think about it, both of them had a tremendous run for Hollywood stars to have that many second chances.

WW: Is there a way to look at the separate legacies of Andy Griffith, Don Knotts and The Andy Griffith Show, or are they too intermingled?

DDV: Andy has this big legacy. He won the Medal of Freedom, which is what Johnny Carson won, so his fame transcends any genre. Don is this huge name among comedians, among standup comedians. He won five frigging Emmys for the same character, and the last two were for guest spots. That’s how beloved he was in that role of Barney Fife. So he is a massive icon among anybody who’s ever done a standup set. I see him as a link in this chain that goes forward from Groucho Marx and Bob Hope, Jerry Lewis, Woody Allen, Don Knotts, Bill Cosby up to the present. And the show, as I’ve said, as you’ve said, has this massive outsized reputation. I don’t think that, unfortunately, many literati in New York and LA think of it as one of the all-time shortlist best TV shows in history. But I think that the show’s accomplishments speak for themselves. If you put something in a time capsule to show future generations or people on Mars, what Americana is, you put in a videotape of The Andy Griffith Show.