Sanford and Son left behind a forever-altered television landscape when its final episode of aired on March 25, 1977. It was immensely popular, of course, but the show also broke new ground in the depiction of minorities on screen and settings that actually reflected the lived experience of a great number of Americans.

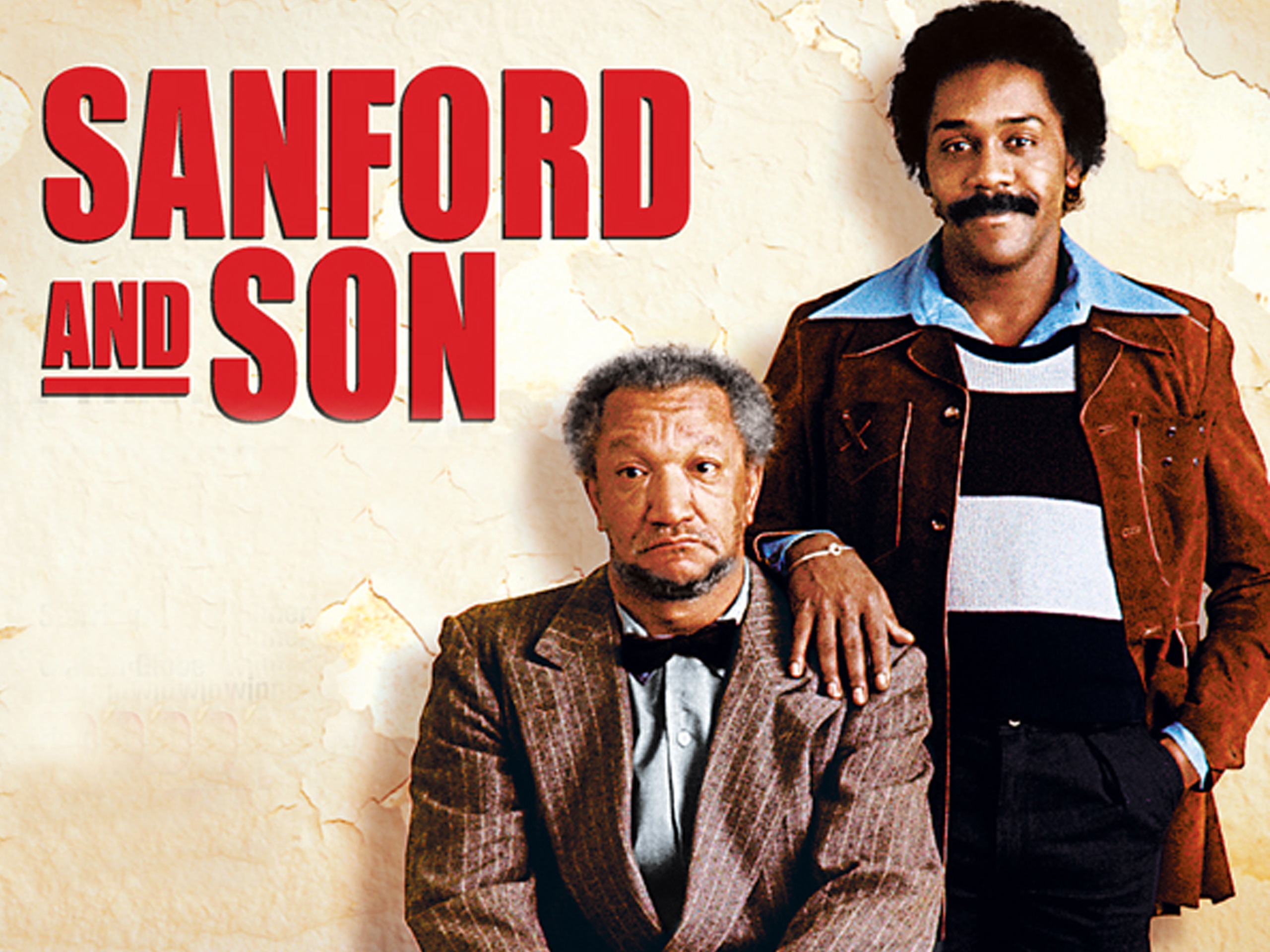

Debuting in January 1972, Sanford and Son followed the escapades of Fred G. Sanford (Redd Foxx), a junk dealer living in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles, and his grown child Lamont (Demond Wilson). The program made an immediate star of stand-up comic Foxx, who’d cut his teeth working a network of Black-owned nightclubs in the South and Midwest referred to as the “chitlin’ circuit.” Sanford and Son also made a name for itself by foregrounding issues of race.

Nearly all of the main and recurring characters were people of color, and like All in the Family – both shows were produced by Norman Lear – it refused to shy away from issues of racism in the U.S. Instead, Sanford and Son forced its characters and audience to engage with these issues through both dialogue and storylines.

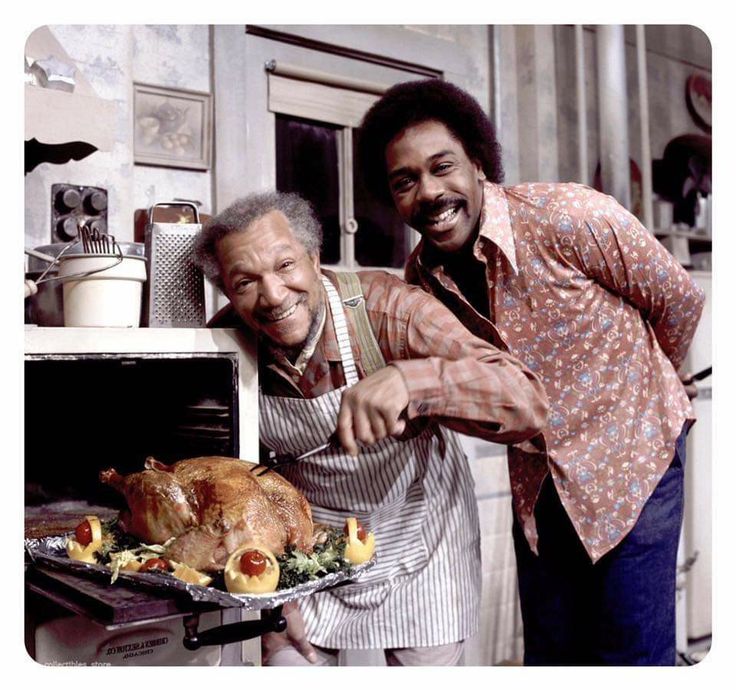

Blending comedy and realism, the show was one of the first to depict the kinds of neighborhoods that many people of color lived in. Before Sanford and Son, a place like Watts wouldn’t often find a home on the television screen. In this way, the plight of Black Americans formed a constant backdrop in the show. Yet at the same time, Fred himself wasn’t above making derogatory comments about the Asians and Latinos also living in his community.

The result was a show that not only focused on the Black experience, but acknowledged how complex the issue of race in America can be – and Sanford and Son did it all by making people laugh. Never preachy, the program used punch lines to point out both differences and commonalities among people, often through conflicts between the cantankerous Fred and his more liberal son Lamont.

As it had been in All in the Family, the recipe was immensely popular, and Sanford and Son ended up in the Top 10 of national ratings for five of its six seasons on air. But beyond its popularity, the show also helped create seismic changes the way that television was made in the U.S., and the kind of people it showed.

One of the key ways Sanford and Son did this was by hastening the introduction of Black creatives into Hollywood writing rooms, which until the ’70s had been dominated by whites. A telling anecdote from writer Ted Bergman helped explain why this change was so necessary.

Bergman penned a Sanford and Son episode in which Fred was playing Monopoly with a friend, leading to a line in which Fred exclaims that the board game was the only place in America where a Black man could own a railroad or a hotel. Foxx nixed the scene, however, because he said “Black people don’t play Monopoly.” No matter how funny or revealing a scene might be, if it didn’t reflect the Black experience it wouldn’t be true.

Read More: 45 Years Ago: ‘Sanford and Son’ Ends, Leaving TV Changed Forever | https://ultimateclassicrock.com/sanford-and-son-finale/?utm_source=tsmclip&utm_medium=referral